Framing Peace: The Impact of Visual and Auditory Arts on Decolonial Education in South Africa

The South Africa project is led by Professor Ashley Gunter at UNISA, with Dr Lorna Christie as the Research Associate. The UNISA team works in partnership with Professor Stefanie Kappler at Durham University.

Introduction

As with many other African countries, South Africa is also a former colony, that faces an intersecting and overlapping form of conflict, specifically refugee-host community tensions (Xenophobia). South Africa is host to over half a million refugees and asylum seekers, many from the most conflict-affected countries in Africa. The influx of refugees into South Africa has led to significant conflicts between local communities and foreign nationals. The xenophobic incidences have progressively got worse over the last few years, with conflict coming to a dire situation in 2019 specifically. Although refugees have access to schooling and government-funded university places, this occurs within the context of historical deprivation of local black populations.

Peace education has fostered cross-cultural engagement in communities, to reduce conflict (Murithi 2009) and to empower locals, specifically women (Mahlomaholo 2010) but few secondary or higher education institutions have incorporated these methods (John 2018). This project specifically focusses on the inner-city suburbs of Johannesburg which has a significant concentration of refugees and immigrants who by their geographical situation are constantly faced with questions of xenophobia (host community vs immigrant conflict).

Peace Education

Peace education is taught within the South African Secondary Education (SE) curriculum, within the subject of Life Orientation. Most studies and curricula and education programs on peace formation in South Africa are focused only on racial relations in the country. This curriculum specifically focusses on the Apartheid system of South Africa, and the implications thereof. Although such information is imperative, the South African curriculum shows a clear gap in peace education with regards to the current contextual conflict situation in which the country finds itself in, namely immigration and regional relations, as well as regional citizenship. The research that the South African team has undertaken to further the peace education initiative has to form part of a decolonial narrative.

Decolonial Approach

The traditional method of teaching and learning has found roots in the exclusive use of written language from the Global North perspective. Although there is value in such literature, historically, Africa holds a culture of story-telling in terms of educational means.

The role of art has long been recognised for its value in connecting people, healing divides and building peace. New materials generated within local communities, that are representative of their knowledges and values, which are paramount to the African narrative, are yet to be embedded in teaching materials to support those most affected by conflict. The arts also allow for the powerful expression of the idiosyncracies and individuality of group identities and cultures, which can be incorporated into teaching to contextualise materials and elevate the learning experience. The project therefore undertook such storytelling initiatives in the form of Soundscapes and PhotoVoice.

Project Methodologies

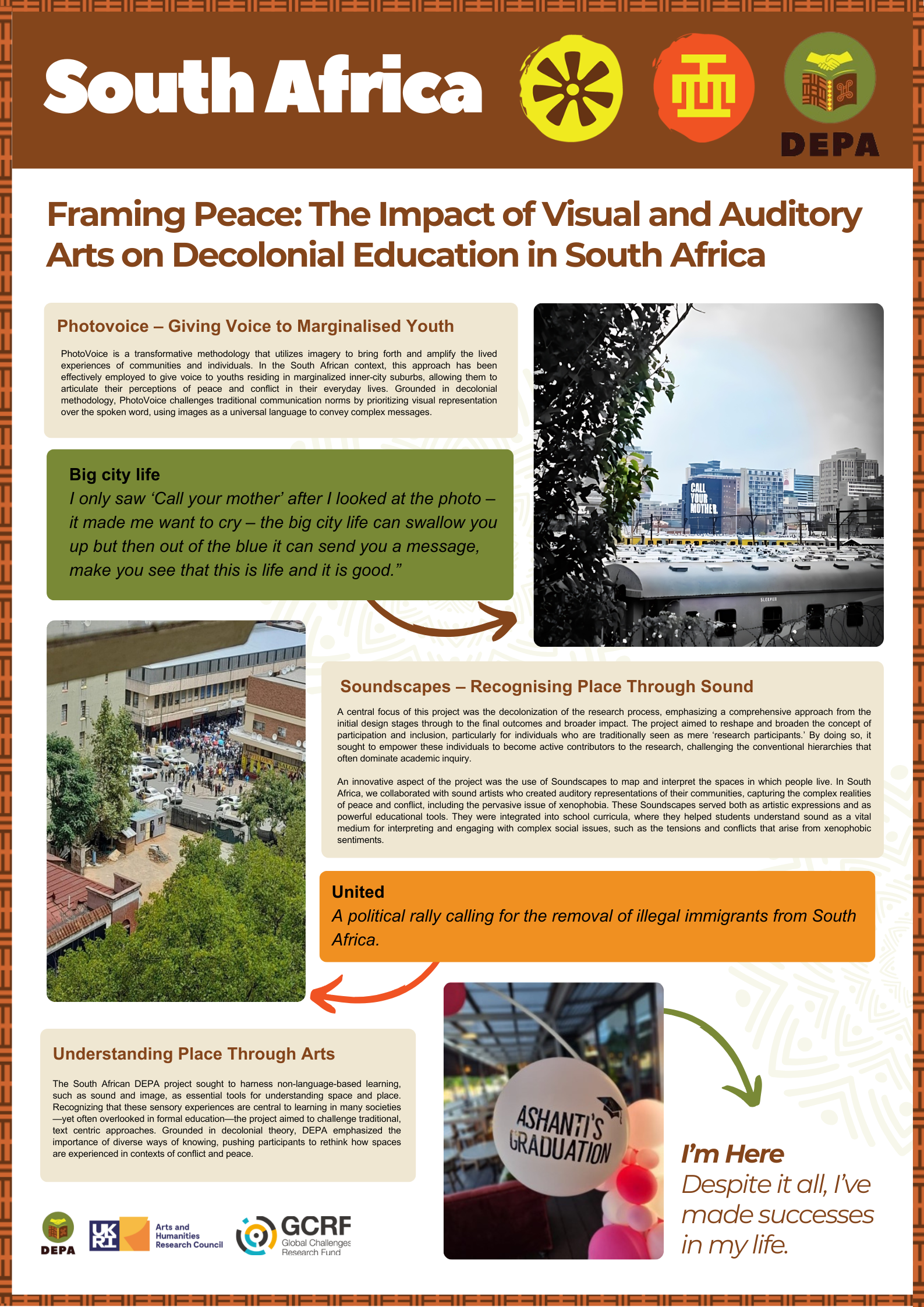

1. PhotoVoice

The DEPA PhotoVoice Project in South Africa sought to empower the youth living in the townships surrounding Johannesburg, offering them a lens—quite literally—to view and depict the intricate socio-political dynamics affecting their communities. At its core, the PhotoVoice Project was a form of participatory visual storytelling. It asked young people to use their smartphones as tools for social critique, capturing elements of peace and conflict in their daily lives through the medium of photography.

Given that Johannesburg's townships are often perceived through a narrow lens of poverty, crime, and unrest, this initiative provided the youth with an opportunity to reframe the narrative. The power of the PhotoVoice Project lay not just in the images themselves, but also in the perspectives they revealed—a juxtaposition of resilience and struggle, of unity and discord, all seen through the eyes of the next generation. As part of the project, the youth participants were encouraged to snap photographs that spoke to them, whether it was a moment of community solidarity, the visible impact of systemic inequity, or an instance of violence. The photos ranged from captures of vibrant street art that articulated community aspirations, to more somber subjects like deserted playgrounds or vigil memorials, each telling a unique story of the circumstances that shape peace and conflict in their lives.

My Secret Place, South Africa

Once the photos were collected, they were displayed online due to COVID-19 restrictions, creating a virtual gallery that was accessible not just to local communities, but to a global audience. This digital exhibition was then complemented by interviews with the young photographers, providing a narrative depth to the visual stories. The interviews offered insight into the thought process behind each snapshot, deepening the impact and broadening the interpretive scope for viewers. The influence of the DEPA PhotoVoice Project extends beyond its immediate participants and viewers. It serves as a compelling visual archive that documents the current realities and future hopes of Johannesburg's townships. By centering the voices of the youth, the project adds a layer of authenticity and urgency to the ongoing discourse on peace and conflict within the region. Moreover, it challenges viewers to engage empathetically with the complexities of life in these communities, inviting them to be part of the larger conversation on social justice and peace-building.

In a world inundated with images, the PhotoVoice Project demonstrates the enduring power of photography to provoke thought, inspire change, and most importantly, to empower the youth as agents of social transformation in their communities.

Objective

The main aim of the PhotoVoice Project was to empower youth in townships surrounding Johannesburg to capture and share visual narratives about the factors influencing peace and conflict in their communities.

Participant Selection

Youth from local townships were invited to participate, with selection based on age range (18-35 years old) and willingness to engage in the project. They were recruited through local community and church groups.

Data Collection

- Photography Assignment: Participants were instructed to use their smartphones to take photographs representing peace and conflict in their daily lives.

- Digital Submission: Due to COVID-19 restrictions, all photographs were submitted online for a virtual gallery.

- Community Reach: The gallery was shared via social media platforms and local WhatsApp groups to engage the community.

Interviews

Youth participants were interviewed remotely to provide context and explanations for their selected photographs.

Data Analysis

Image Coding: Each submitted photograph was subjected to a thematic coding process, wherein recurring elements and motifs were identified. These themes included but were not limited to, elements like community, isolation, violence, unity, and resilience.

Community Feedback

Online reactions and comments were analysed to assess community perception and engagement.

2. Soundscapes

The Soundscapes Project for DEPA in South Africa reverberated through the bustling, multicultural inner-city suburbs of Johannesburg, capturing both the complexity and dynamism of a community often overshadowed by violence and xenophobia. A region rich with a blend of local and immigrant communities, the auditory canvas of Johannesburg is as diverse as its people. In a nation where sound has historically been an instrument of resistance, resilience, and cultural exchange, the Soundscapes Project was more than a creative endeavour—it was a sociopolitical statement.

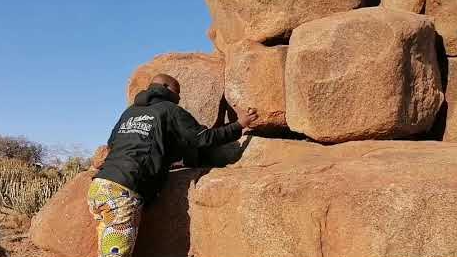

Volley Nchabeleng, award winning musician creates music with rocks

The project invited local artists to curate soundscapes that reflected the dual themes of peace and conflict, giving them a platform to express their individual and collective experiences. Each soundscape was a carefully woven tapestry of emotions and stories, encapsulating the tension and harmony that characterises life in these vibrant communities. The project was realised in the middle of the COVID-19 lockdown, which made the endeavour more challenging but also uniquely relevant. Unable to host live performances, the project innovatively leveraged digital platforms, publishing the soundscapes online and disseminating them through WhatsApp groups to ensure widespread community engagement. Artists involved in the project were then interviewed, providing context and insight into each soundscape. These interviews added layers of meaning and interpretation, helping listeners to not just hear, but understand, the narratives embedded within each auditory composition. From the rhythmic beats that symbolised unity to the dissonant notes reflecting conflict, the interviews demystified the artistic process and intentions, fostering a deeper level of engagement from the community.

Go to Volley Nchabeleng's Music on the Rock

The impact of the Soundscapes Project goes beyond the auditory experience. It serves as a sonic archive of contemporary social issues, encapsulating the emotions, hopes, and struggles of a community in flux. It also functions as a catalyst for dialogue and reflection, challenging listeners to confront and reconsider their preconceptions about peace, conflict, and the fabric of their community. In a landscape marred by violence and division, the Soundscapes Project resonates as an artistic beacon of resilience, fostering unity through the transformative power of sound.

Objective

The primary objective of the Soundscapes Project was to capture and analyze the sonic representations of peace and conflict in the inner-city suburbs of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Participant Selection

Local artists residing in the targeted inner-city areas were invited to participate. Selection was based on previous artistic engagements or community involvement.

Data Collection

Soundscapes Creation: Artists were tasked with creating soundscapes that reflect elements of peace and conflict in their communities.

Digital Platform

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, all Soundscapes were submitted and disseminated online.

Community Reach

The produced soundscapes were shared through community-focused WhatsApp groups to garner local engagement and feedback.

Interviews

Selected artists were interviewed to provide context to their soundscapes. Interviews were conducted remotely and were recorded for qualitative analysis.

Data Analysis

Qualitative Analysis: Interviews were transcribed and coded to identify recurring themes and sentiments.

3. Teacher's Workshops

The South African DEPA team hosted an impactful Teachers Workshop aimed at educators teaching Life Orientation in low-income schools. The focus was squarely on a crucial, yet often overlooked, subject: teaching peace in the classroom. Through interactive sessions, teachers and DEPA experts engaged in a dynamic exchange of experiences and strategies. The outcome of this workshop was a collaboratively developed framework that provided actionable, practical methods for incorporating peace education into the classroom setting. Ideas ranged from curriculum adjustments to hands-on activities designed to foster empathy and mutual respect among students. The Teachers Workshop serves as an essential stepping stone in the journey towards a more peaceful educational environment. By equipping educators with the tools and knowledge to teach peace effectively, DEPA aims to sow the seeds of change from the ground up, starting in the classroom.

Objective

The primary goal of the Teachers Workshop was to engage educators teaching Life Orientation in low-income schools to share experiences and collaborate on effective methods for teaching peace in the classroom.

Participant Selection

Teachers from schools classified as low-income were invited to participate. Selection was based on their current roles in teaching Life Orientation and willingness to engage in the workshop.

Data Collection

- Interactive Sessions: The workshop featured interactive activities and discussions between teachers and DEPA experts, focusing on experiences and challenges in teaching peace.

- Framework Development: Participants collaboratively worked on developing a practical framework for teaching peace in their respective classrooms.

Data Analysis

- Qualitative Feedback: Teachers' input during interactive sessions was documented for thematic analysis.

- Framework Assessment: The developed framework was reviewed and refined based on participants' expertise and suggestions.

The South Africa Project poster from the DEPA Event

Project Highlights

The DEPA project in South Africa brought to light the transformative power of integrating arts and education in addressing social issues. One of the key learnings was the effectiveness of visual and auditory storytelling in capturing the complex narratives of peace and conflict within communities. The engagement of youth and local artists in projects like PhotoVoice and Soundscapes not only provided them with a platform to express their realities but also facilitated a deeper communal understanding and dialogue around these critical issues.

Educational Resources

The SA project has innovatively developed a framework for decolonising peace education, aimed at reshaping the narrative and pedagogy around this critical subject. This open educational resource (OER) is set to enrich UNISA's MOOC platform, offering accessible, culturally relevant content that aligns with the African Union's Agenda 2063. The framework emphasises inclusivity and sustainability, preparing educators and learners to contribute to a peaceful and prosperous Africa through education that respects and integrates African values and perspectives. This OER will be available in 2026.

Impact

The collective impact of the DEPA projects in South Africa extends far beyond academic research, resonating deeply within the communities they engaged. By tapping into local artistry, youthful perspectives, and educational insights, the projects catalyzed important dialogues around peace and conflict that transcended traditional barriers of age, profession, or social standing. For instance, the Soundscapes Project led to spontaneous community discussions about safety, while the viral photograph from the PhotoVoice Project inspired grassroots initiatives focused on youth and mental health. Similarly, the Teachers Workshop provided a new framework that has begun to reshape how peace education is approached in low-income schools. These ripple effects showcase the transformative potential of research that is not only multidisciplinary but also rooted in community participation, setting a precedent for how academic initiatives can effectively contribute to social change.

Research “outputs”

The following is envisaged for the avenues of dissemination; however, consultations were held with participants to ensure that relevant avenues for dissemination were used.

For soundscapes, artists performed a concert in a local community hall, further, soundscapes were presented in an OER at Unisa. PhotoVoice images were displayed in an exhibition at the Holocaust Centre in Johannesburg as well as at the Unisa art gallery. The OER will involve dissemination on an international scale, i.e. the OER will be made available on the Unisa library’s repository, and the link to such a resource will be communicated with all relevant stakeholders. It is envisaged that education students should be exposed to such an OER, however, access to the OER will not be limited to Unisa education students only, but will be made available to an international audience. Furthermore, to assist with the dissemination of the content to those who do not necessarily have access to such resources, alternative modes of dissemination are also being investigated.

All of the data collected has been communicated to the academic community at large through publication in academic journals and presentations at conferences, both local and international. The information will further be placed on institutional repositories of Unisa and the OU UK. The language of dissemination is in English, alongside the sound clips and photographs created, but after consultation with the participants, this might be translated into any one of the eleven national languages of South Africa, to reach a larger audience.

The dissemination of the project's findings and creative outputs was multi-faceted, including local exhibitions, online repositories, and academic publications. The PhotoVoice images were displayed at significant venues like the Johannesburg Holocaust Centre, while the soundscapes were shared through digital platforms, reaching a wide audience. These initiatives not only highlighted the current social dynamics but also provided a foundation for further academic and practical exploration in the fields of peace education and decolonial studies.

DEPA South Africa hosted an online decolonial conference on the topical issues of decolonising peace education in South Africa.

Find out more about the Decolonial Conference